Let’s get started on the right foot: Weather and Climate are not the same…

…but it’s easy to see why people confuse the two. For years, scientists have explained how rising temperatures will (and already have) make weather events more intense, more dangerous, and more costly. Then, as time has progressed, what have we seen? A consistent pattern of more intense, more dangerous, and more costly storms. Therefore, in my opinion, we shouldn’t be surprised when people ask, “Was this storm in particular made worse by climate change?”

The answer, it depends on who you ask.

When we talk about climate change, it is imperative to keep in mind that we are talking about trends, not events. This is why people who are careful with their words and value being technically accurate often say things like, “Over time, this, will happen on average as the climate changes.” The reasoning is simple: we can never definitively prove that the conditions enabling a storm, wildfire, or even a season with little snowfall could not or would not have occurred without human-caused climate change. In reality, most extreme weather events we see today still have some historical precedent. Furthermore, even if a new extreme is reached, it doesn’t mean it was physically impossible for that event to have happened before. What we can confidently and factually communicate is this: new extremes—or events approaching those extremes—are becoming easier to reach and more likely to occur.

There are two problems that I commonly see with this approach to using weather to talk about climate. It’s boring and people don’t think that critically. I don’t think this is even slightly controversial. In a deeply fractured media environment, we’ve never had more sources competing for our attention. As a result, the repetition of “the worst is more likely” and showing graphs of rising lines simply doesn’t capture most people’s interest—or make them care—anymore (if it ever did). If someone cannot connect the concept of climate change to a specific instance of death or destruction, they won’t fully comprehend it. Why did scientists ever think that showing the average person a graph and explaining some oversimplified thermodynamics would make them understand the threat well enough to push for drastic change?

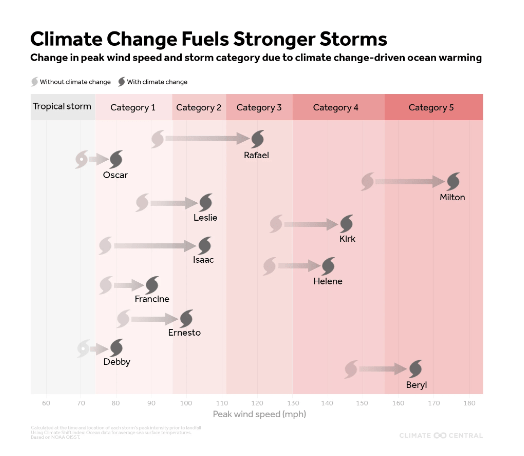

So, what’s the solution? Some are turning to climate attribution studies as a way to communicate information that is both scientifically rigorous and emotionally impactful. Climate attribution science isn’t new—it’s been studied for most of the new millennium—but I’ve noticed it being used more frequently in everyday media. For those unfamiliar, attribution studies use historical weather records and climate models to estimate what a storm or weather event might have looked like if human-caused climate change hadn’t been a factor.

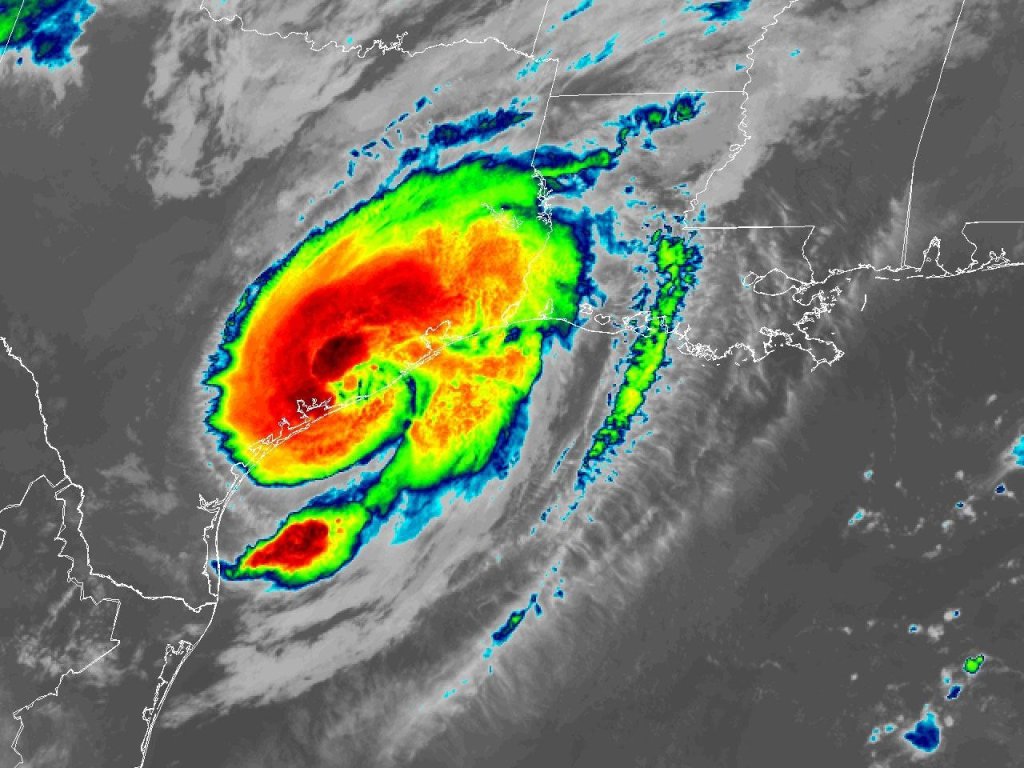

The most recent example of such a study modeled the intensity of 2024 hurricanes if sea surface temperatures (SSTs) had not been influenced by human-driven climate change. Conducted by Climate Change Central, the study found that SSTs were up to 2.5 degrees warmer due to human activity, which led to peak wind speeds intensifying by 8–23 mph for every storm.

So there we go, problem solved! We have away to link climate change to specific events that can be backed by science. War is over! Right? I am not so sure. Like any scientific study, attribution studies have limitations regarding what can and cannot be accurately modeled. That doesn’t bother me as much, however, as how abstract the concept might seem to the average person. In a time defined by record levels of disinformation and widespread distrust in science, I doubt attribution studies will easily make its way into the everyday conversations of your neighbor Joe Schmo.

So if people on the surface we cannot link induvial weather events to climate change, trends are too boring, and attribution studies are too abstract then what is the solution to this communication problem? Beats me, but we at least have to talk about it.

Leave a comment